As a general rule, there is little room to be thoughtful about someone’s life in the immediacy of their transition. What can be offered which isn’t obvious? In that sense, I was debating whether my thoughts on Pelé needed more time on the stove, but he did such a great job marketing himself I’ve had my whole life to think about the Brazilian giant, despite never seeing him play live.

My parents knew I would consume anything about sports. Our house was replete with books and documentaries on legends like Jackie Robinson, Hank Aaron, Jesse Owens, Muhammad Ali, Joe Lewis, and Bill Russell. I first encountered Pelé in a biographical comic my dad brought home. I was maybe eight.

I remember Pelé’s father, Dondinho, a striker who trained his son after suffering a career-ending injury. The panel I best recall is Dondinho telling Pelé to shoot with his left foot. Your right foot will always be good, but to score many goals you need both feet. Pelé’s mother, Celeste, didn’t want her son pursuing football because of what befell her husband. The attraction of being like his father proved too much, so Pelé didn’t listen, but he used the warning as motivation. Football was not for vanity, it was to support his family.

The story was memorable. A poor boy from Brazil conquered the world three times and became the greatest. His natural gifts the fuselage, his father’s drive the engines, and his mother’s material condition the wings.

With basketball, baseball, boxing, athletics, and American football dominating most places I grew up, I wasn’t surprised to discover an African from Brazil as the greatest in his sport. Why should that be shocking? Pelé was simply added to the list of greats I already knew. No patterns or perceptions were shattered in my mind. If anything, there was consistency.

It took learning football’s universal appeal, the World Cup’s gravitational pull, and how Africans are generally viewed in Western countries where football is primary for the concept to assume new meaning.

An exciting topic at university came too late. I would’ve studied it further, but the sands of time had run out. Upon learning I was a football fan and came from mixed parentage, a sociology professor told me during office hours to research something called the “Mongrel complex.” Hearing the term made my face cringe, but he said to trust him.

[In that same way, if you made a face, trust me, it requires the smallest foundation.]

The 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s were a time of upheaval in the African world. Many countries on the continent were given independence. Freedom movements were either beginning (e.g. the United Kingdom) or reaching their climax (e.g. the United States). The Pan-African gospel of Marcus Garvey contained within the human rights struggle of Malcolm X was found in Black nationalist formations springing across the Diaspora. It must have felt as if the African world was shifting but had not yet turned (sadly, it remains so).

Brazil was no different. With the largest population of Africans in any country not named Nigeria (whether they accept the label is its own thing, but the continent has a way of leaving its mark), Afro-Brazilians in the 20th century created structures to establish Diasporic solidarity and redress the domestic effects of colonisation. These aimed at affirming and amplifying the cultural importance of Black Brazilians. The Teatro Experimental do Negro (1944-1961) and the Associação Cultural do Negro (1954-1976) as two examples.

The “Mongrel complex” was a term invented by Nelson Rodrigues. The Recife-born novelist and playwright defined it as:

The inferiority in which Brazilians put themselves, voluntarily, in comparison to the rest of the world. Brazilians are the backward Narcissus, who spit in their own image.

Here is the truth: we can't find personal or historical pretexts for self-esteem.

Undergirding Rodrigues are enslavement and colonisation. Millions of Africans were transported to Brazil during the transatlantic slave trade, and once there a multicultural exchange occurred with indigenous peoples and European colonists. Rodrigues’ idea supposes the former Portuguese colony may be psychologically broken when placed in conversation and competition with those less multicultural.

If the complex is an accurate diagnosis of how Brazil understands itself, it leads to the conclusion Africanity is somehow a corrupting factor, an explanation for failures that manifest on the global stage, leaving behind embarrassment and shame. This communal lack of self-esteem partially explains why the Black Brazilian movement wanted to insert itself in the cultural, social, and political milieu, combating deeply-rooted anti-African beliefs permeating society.

The football connection is Rodrigues wanted to explain the devastating cognitive blow his country suffered after losing the 1950 World Cup final. Stumbling in their own backyard to Uruguay, it is Brazilian football’s most damaging encounter (only the 2014 World Cup semi-final against Germany compares). The scapegoats were the Afro-Brazilians, starting goalkeeper Barbosa above all.

Amid the psychological crisis created by O Maracanaço (the Maracanã Smash), Pelé emerged in 1957 looking like he looked and playing like he played.

Internal questions concerning the capacity of Afro-Brazilian footballers were largely put to rest after Sweden in 1958. Brazil won three World Cups in four editions. Santos toured the globe, beating Inter Milan, AC Milan, Juventus, Barcelona, Lyon, Chelsea, and Benfica in select friendlies. Labelled O Rei (the King), Pelé was declared a national treasure and prevented from leaving Brazil to play in Europe. The sport grew rapidly as television increased in popularity. The forward became the face of football, the World Cup, and Brazil—at least outwardly.

His career converged with the Brazilian military coup d’état of 1964. Standard with coups sponsored by the United States and the United Kingdom, the installed regime was authoritarian and right-wing, using nationalist fuel to drive their project. The chief propellant of nationalism in Brazil was (and remains) football. President Emílio Garrastazu Médici used the 1970 World Cup campaign and triumph for positive publicity. While forwardly embracing Black footballers, the junta was adept at ignoring the plight of everyday Africans in the background. Afro-Brazilians on the national team were caught in a precarious middle.

In Michael G. Hanchard’s Orfeu e o poder: o Movimento Negro no Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo (2001)—the Portuguese print of Orpheus and Power: The Movimento Negro of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo (1998)—the UPenn Africana Studies professor wrote:

During the 1970s and 1980s, Afro-Brazilians who imbued their expressive activities with explicit protest and condemnation of the situation of Blacks in Brazilian society were frequently censored, in formal or informal terms, by elites who saw such accusations as an affront to the national character.

Activists like Abdias do Nascimento—Brazil’s foremost Pan-African thinker and founder of the Teatro—were forced into self-exile to avoid further damage. In exile, he published the first edition of Brazil, Mixture or Massacre? (1979). Taken from the second edition (1989), Nascimento explained:

Since 1950 race and color data have been omitted from census information in Brazil on the assumption that an act of ‘white magic’ can eliminate ethnicity by decree. This process occurs under the rationale that it is founded on a precept of social justice—everyone is a Brazilian, be he Black, white, Indian or Asian. But its real significance is that it provides another instrument of social control. The reality of race relations is masked, and any information that Blacks could use in their struggle for social justice is withheld.

It represents the attitude that any movement by Afro-Brazilians toward consciousness of our own situation, any desire to clarify our understanding of our own history and experience, is seen as “a threat to national security,” an “attempt to disintegrate Brazilian society and national unity,” or worse, as “retaliatory aggression and a call for imposition of a supposed Black superiority: reverse racism.” Thus every effort is made to obstruct informational channels, isolating and marginalizing us as a group. For the outcome of such practices is to negate any racial, ethnic, or cultural definition of Black people, denying us any collective identity.

The Black athlete is not obligated to speak. Being an African is required, sure, but is not solely sufficient. Only the politically competent should speak on behalf of the people—whether an athlete, actor, teacher, writer, doctor, lawyer, student, bus driver, or whatever.

Though the table was set for the most famous athlete in the most popular sport, Pelé was not of himself political. The politics of race and representation projected onto him were not necessarily his. Pelé’s existence serves as a platform for dialogue, but his manoeuvrability within that history was limited. Not standing against a military regime is entirely understandable. He would’ve been scythed down faster in the political arena than he was on the pitch.

Danger exists in the political. Safety exists within greatness. Only in rare instances do athletes excel in their sport, reach levels of fame and education where they can positively politicise the masses, then act upon that reality. Pelé was happy to stay within the confines of greatness and reap the rewards. When it was feasible in the mid-1980s to support Diretas Já (Direct Now) and call for immediate presidential elections, Pelé was able to wiggle, but wanting him at the junta’s height to martyr himself is perhaps too Biblical—even for Brazil.

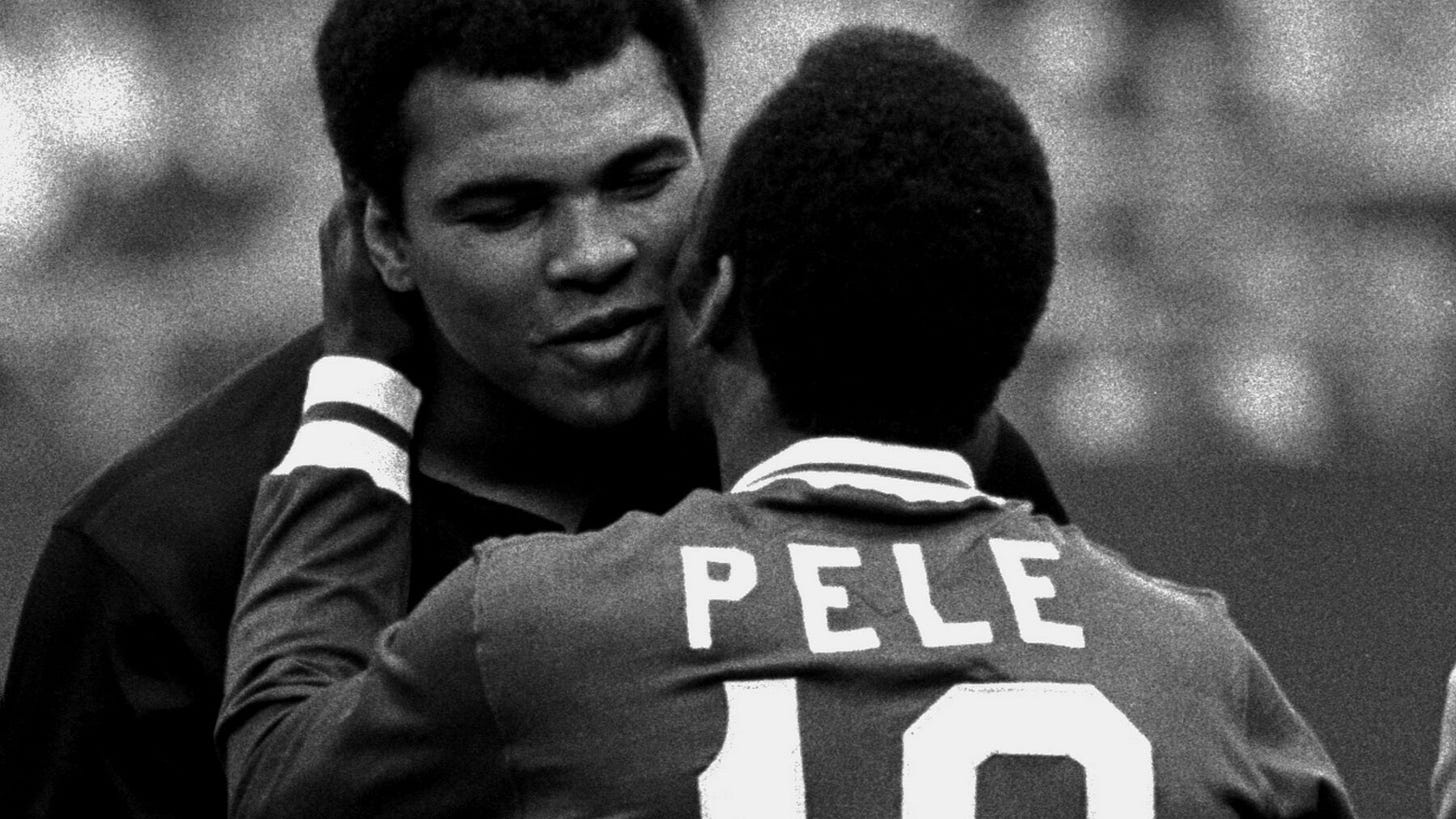

He wasn’t Ali, who was politically articulate and willing to be crushed in the moment. Neither was he Michael Jordan, who won’t touch anything political with a barge pole. Pelé found himself in the median, surviving through governmental mutations. Greatness was his voice in every instance, but if you asked him about race he was happy to give whichever answer fit the bill.

Since his passing I’ve thought about what it means that Brazil’s titular king is an African, but nary an African can be found when looking through Brazilian heads of state from 1500 to 2023.

Pelé as O Rei was optically advantageous for Brazil in every era, and that will continue after his death. A country with an African face whose government treats Afro-Brazilians as second-class. Some would say: Who better to speak than the king, but he was only ever king on the pitch.

Football affords many things, but it can’t be more powerful than the society giving it meaning. Sport is an appeasement, not tool for politicisation. Brazil’s cultural identity is so consumed by the game Pelé was given the status of king, but without the power (influence, maybe, but power is altogether different). Like everywhere, Africans in Brazil are used for their ability to act, sing, dance, fight, run, jump, or think and rewarded as individuals, while austere politics and general contempt conspire to stifle their collective uplift.

As one living outside Brazil, it is hard to place exactly what Pelé could have done internally. After military rule perhaps elevating his voice and the voice of other Afro-Brazilians in a more forceful way, but his function wasn’t orchestrating the Pan-African revolution. Often plucked from poverty and given access to wealth, becoming a instrument for capital is the endgame for most footballers; the sport isn’t designed to do anything else. He was a billboard for Puma, Pepsi-Cola, and Viagra, not a disciple of Garvey or Che. Unless hypocrisy is apparent, I’m loathed to criticise someone for taking the path designed and incentivised for them—I’m sympathetic to the programming and the temptation.

By virtue of the era in which he played, Pelé being an otherworldly footballer was his victory. Brazil and the world needed to see someone like him excel in a sport predicated on speed of thought and technical prowess, then be willing to assert his Africanity, or at least not openly reject it.

Heralded for his goalscoring, Pelé’s ultimate triumph is passing to generations of Africans, who may have felt it unattainable, proof it was indeed possible to be great—even “the greatest.” 🎯