On the list of things European football should consider borrowing from American sport, the Rooney Rule is always popular.

Named after former Pittsburgh Steelers owner Dan Rooney, the rule demands each National Football League (NFL) team, when looking for prospective coaches and general managers, interview non-white candidates. Its stated purpose is expanding the pool of viable applicants historically excluded from the hiring process.

Expanded two years ago, the NFL requires “every team interview at least two external minority candidates for open head coaching positions and at least one external minority candidate for a coordinator job. Additionally, at least one minority and/or female candidate must be interviewed for senior level positions.”

It stops short of establishing quotas; it merely constructs hoops for teams to jump through—and NFL franchises have become adept leapers. Using data from the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport published last year, one can imagine the NFL’s hiring practices like a five-level pyramid.

At the base, African players comprise roughly 60 percent. Above players are assistant coaches, where Africans represent 36.3 percent. Head coaches make the third level. When the Rooney Rule was enacted in 2003, the NFL employed three African head coaches—9.4 percent—and that figure remains the same in 2023. Combine general managers with presidents and chief executive officers to create the fourth level. There are 11 Africans in the 64 available positions—17.2 percent. Ownership is the top, where there has never been an African owner (limited partners, sure, but never ownership outright).

After two decades of implementing the Rooney Rule, Africans have not gained one head coaching position. Years existed where the number was higher than three, but never close to reflecting the African talent concentrated to play. The NFL has tried to rectify the disparity; and their failure in that aspect serves to highlight a tenet of institutional racism: power will not create space for those it deems inferior.

In Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (1967), Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton coined the phrase “institutional racism,” which they defined as overt and covert acts of racism “by the total white community against the black community.” The co-authors explained deeper:

Institutional racism relies on the active and pervasive operation of anti-black attitudes and practices. A sense of superior group position prevails: whites are “better” than blacks; therefore blacks should be subordinated to whites. This is a racist attitude and it permeates the society, on both the individual and institutional level, covertly and overtly.

“Respectable” individuals can absolve themselves from individual blame: they would never plant a bomb in a church; they would never stone a black family. But they continue to support political officials and institutions that would and do perpetuate institutionally racist policies. Thus acts of overt, individual racism may not typify the society, but institutional racism does—with the support of covert, individual attitudes of racism.

After quoting Charles Silberman’s Crisis in Black and White (1964) on how the “dilemma” concerning race relations in the United States was not a true dilemma in a moralistic sense for white America, but rather the disruption of their peace and business interests, Ture and Hamilton followed with:

There is no “American dilemma” because black people in this country form a colony, and it is not in the interest of the colonial power to liberate them. Black people are legal citizens of the United States with, for the most part, the same legal rights as other citizens. Yet they stand as colonial subjects in relation to the white society.

Thus institutional racism has another name: colonialism.

Notions of internal colonialism must connect when thinking about the conditions of African people, not just in the United States but anywhere in proximity to Western power. If looking at hiring practices, one must consider which institution has its hands on the mechanisms of control, which individuals comprise the institution, and what group is attempting to enter.

In athletics there is no question on the use of African bodies to generate profit. That is a clear extension of colonial relationships. There is always room for those who jump high, run fast, and tackle hard. Once the body deteriorates and the task becomes thinking, the opportunity for bias arrives. A 40-yard dash isn’t biased; value is determined by the stopwatch. When merit comes from what exists inside the mind, centuries of disinformation about the cognitive ability of African people is well documented, and what is a coach if not a thinker?

The Rooney Rule is ineffective because it does not mandate change nor decision makers to undergo brain transplants. The rule asks billionaire owners to briefly pause their plan to speak with someone they know won’t be hired. The racist attitudes permeating society don’t disappear because you interview African candidates. If they did, after decades and hundreds of interviews conducted in the league that invented the protocol, the count wouldn’t remain at three. Something at the ownership level doesn’t see African coaches as viable or actionable. Ture and Hamilton voiced that something in 1967.

The dynamic doesn’t change across the Atlantic Ocean.

As reported by ESPN’s Mark Ogden, the Premier League’s chief executive Richard Masters told reporters the Rooney Rule “hasn't been a topic of discussion and we have no plans to put it back on the agenda.”

Masters added: “Lots of organisations have diversity targets and we all consider them. There is going to be an ongoing dialogue with clubs about discrimination generally and I think it's an important topic. What's most important is that there are no barriers to entry. The pipelines for employment in coaching are free."

The English football pyramid has 92 managerial spots in the men’s game. Six of them are filled by African people: Vincent Kompany (Burnley), Liam Rosenior (Hull City), Paul Ince (Reading), Sabri Lamouchi (Cardiff City), Darren Moore (Sheffield Wednesday), and Dino Maamria (Burton Albion).

After Crystal Palace sacked Patrick Vieira on 17 March, the number of African coaches in the Premier League returned to zero; it seems “there are no barriers to entry” except the barrier to entry.

Forty-three percent of Premier League players and 34 percent of Football League players are African, according to the Szymanski Report commissioned by the Black Footballers Partnership. It cannot be argued Africans don’t participate in the sport, yet their participation does not translate upward and isn’t taken seriously by those deciding who stands on the touchline.

That process requires connecting the same dots. Africans in the United Kingdom are an internal colony. Nominally included in the whole, they wear the trappings of citizenship and may be used to sprint, tackle, dribble, shoot, or score, but—to take from Ture and Hamilton—it is not in the interest of the colonial power to liberate its colonised. Unless and until the power dynamic between African people and those in power are rearranged, the same systems of oppression will continue.

The Rooney Rule is incapable of changing racist arrangements and sentiments in board rooms. Its function is exposing the system as anti-African. On that level, I’m careful not to dismiss the rule as unnecessary. It is simultaneously necessary and inadequate. Indeed, it is the inadequacy that makes it necessary.

The path forward requires working to detach self-worth and self-respect from the amount of hostility one can withstand in the face of hostile systems. There are countries full of African coaches. If an African must coach there is no lack of love for football on the continent or throughout the Diaspora—so shelter can be found; it is a matter of seeking refuge where it is offered.

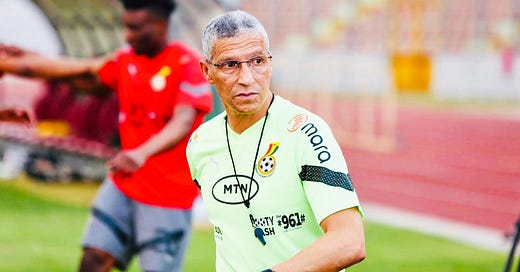

Taking that line, former Newcastle, Brighton, and Nottingham Forest boss Chris Hughton is currently head coach of Ghana’s national team. His first two games coaching the Black Stars were against Angola during the international break. Taking four points from six, Hughton is destined for Ivory Coast next January at the 2023 Africa Cup of Nations.

[Don’t ask why it’s called “AFCON 2023” when the games are in 2024…]

Born to an Irish mother and Ghanaian father, he has pulled from both branches. Hughton played internationally for his mother’s country (the first African to play for Ireland, earning 53 caps), and his present post covers the roots given to him by his father. His club and managerial careers took place largely in England until Ghana hired him as technical advisor then full-time boss.

Avoiding notes of imperialism must be contended, where those born outside the continent—despite their visage—come to mimic behaviours found in the empires they were raised. One cannot be deaf to the colonial undertone of “man born in England managing Ghana” nor the colourist undertone of “mixed-race African managing Ghana,” but the idea of Hughton taking concepts learned in the Premier League and manifesting them in the African arena rings true.

The Black Stars could easily embarrass themselves at AFCON 2023, the temperament of Ghanaian football is erratic in that way, but Hughton has stumbled upon something I’ve always considered. American football is too insular. Its reach isn’t global, but the universality of football (association) is unrivalled. No matter where, people play the game in an organised manner, and organisation necessitates coaching.

Diasporic coaches establishing networks across African, South American, and Caribbean countries—as well as internal colonies in the heart of empire—to organise where coaches are, who needs their services, and which places are best equipped to hire and train them without overwhelming existing infrastructures seems the prudent course.

If the mission is lobbying European leagues to enact more equatable hiring practices with an impotent Rooney Rule, that time and energy could be better spent. Solutions cannot—and will not—come from those entrenched in systems of white hegemony. They must spring forth from within African people.

“African” used throughout in the pan-African spirit of Ghana’s first head of state, Kwame Nkrumah: “I am not African because I was born in Africa, but because Africa was born in me.” 🎯

The bit about the black body being used for profit and then when the body detoriates and thinking matters more, reminded me of the Jordan Peele film Get Out. If you've seen it, you'll know what I mean. 😂 Great piece!

Great insight and read. Thoroughly enjoyed it